In 1915, prominent American palaeontologist, Henry Fairfield Osborn, published Men of the Old Stone Age: Their Environment, Life, and Art. Drawing from his three-week-tour of archaeological sites across Paleolithic Europe, Osborn’s book integrated archaeology, geology and prehistory. Painstaking in its scientific detail, Men of the Old Stone Age also offers a beautiful collection of early-twentieth century illustrations of landscapes, fauna, and hominins from renowned paleo-artists Charles R. Knight and Erwin S. Christman.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, artists, scientists, and museum curators worked closely to create the most real or true-to-the-fossil record reconstructions of long-extinct animals. As the president of the American Museum of Natural History, Osborn was well-situated and sought Knight’s artistic expertise to provide illustrations for Men of the Old Stone Age. Knight, who had already contributed many dinosaur murals to the very same museum, was eager to participate in Men of the Old Stone Age and many of the illustrations in the book have become iconic of the Pleistocene – even emblematic of how early twentieth-century paleo intelligentsia thought about the epoch.

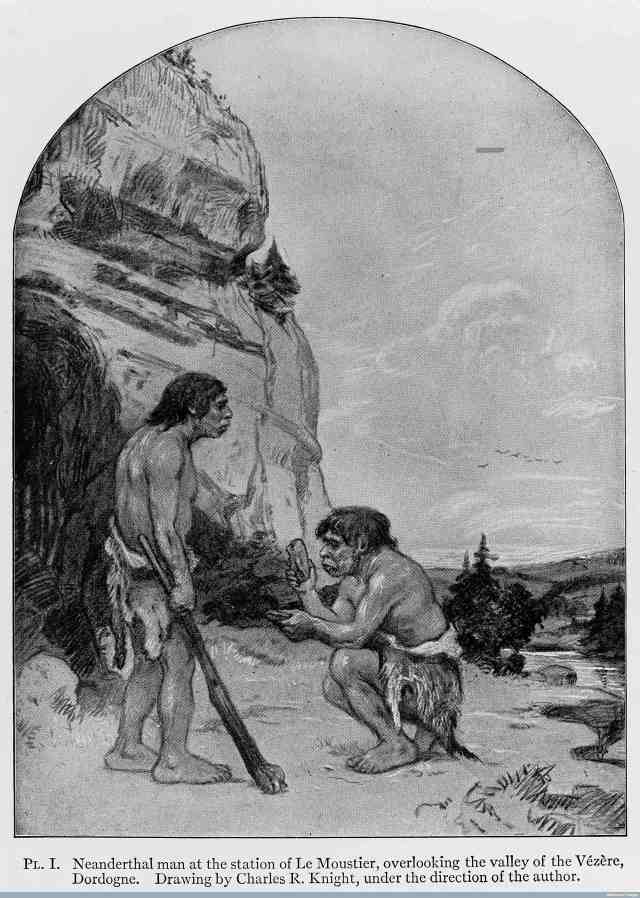

Neanderthals at Le Moustier (Art by Charles Knight, 1915. From Welcome Images)

While reconstructions of taxa vied for authenticity and scientific accuracy, artists like Knight understood that the inherently incomplete, and even scrappy, nature of the fossil record left a lot of room for imagination in reconstructed landscapes and species. He recognized that how people imagined and made sense of long-extinct landscapes of the Pleistocene depended largely on his art and others’ science.

It’s hard to not have a subconscious connection to Charles Knight’s artwork, whether you know you do or not. I would venture to guess that just about any paleo-enthusiast, Pleistocene or otherwise, has walked across a museum exhibit backstopped by one of Knight’s paintings. Even palaeontology icon, Stephen Jay Gould, used two of Knight’s dinosaur prints for book covers and gushed that Knight’s artistic skill and vision were unmatched in the paleo world of imagined landscapes. The paintings are familiar, yet the origins are not.

In early nineteenth century landscape painting, artists painted idealized, romanticized, representations of the landscapes they were looking at. The paintings were realistic and the genre demanded attention and faithfulness to detail. This was all fine and good for a era of landscape realism, but how could one paint a landscape long-since extinct. How does an artist “credibly present the form, action, and environment of any fossil creature,” to quote Knight, with the fossil record’s inherent incompleteness?

By the end-of-the nineteenth century, however, landscape artists utilized growing impressionistic trends to soften lines, emphasize sweeping movement, and to embrace colour. This impressionism provided a key artistic schema for Knight’s work and quickly signified his style. The impressionists’ techniques allowed for a believability of imagined space – and such techniques would be useful in the reconstructions and abstractions of a palaeoenvironment. Moving away from harsh pen-and-ink sketches, Knight’s watercolored and impressionistic landscape paintings illustrated extinct species living in idyllic, Eden-esque environs. The lines in Knight’s Pleistocene paintings are soft, the colours muted, and the tone transcendental.

The infamous sabretooth cat Smilodon populator, standing at the edge of a cliff, roaring. (Art by Charles Knight, 1905. From here)

In one such painting, the portrait of Smilodon, Knight draws on the viewer’s familiarity with big cats, but creates subtle differences. The familiar back line of Smilodon catches the viewer’s eyes – the line of the cat’s back, emphasizing its shorter front legs and powerful neck – and cuts across the painting. In the glorious painting, Mammoths, the viewer anticipates the mammoths’ journey toward the sun, low on the mural’s horizon. The hovering, warm light begs the question of whether the mammoths are walking toward a new horizon, depicting the migration of the herd walking toward a sunrise, or whether the proboscideans are walking toward their extinction, a sunset on the landscape. Henry Fairfield Osborn considered Mammoths, painted in 1916 for the Hall of the Age of Man at the American Museum of Natural History, to be Knight’s magnum opus.

Woolly Mammoths marching through the snow near the Somme River in France. A mural painted at the American Museum of Natural History. (Art by Charles Knight, 1916. From here)

Knight’s work with prehistoric man, offers a more complicated narrative of hominin evolution than one might expect from the early twentieth century. Knight’s use of natural light, his emphasis on movement within the scene, and a commitment to colour highlights the natural and impressionistic undertones of his work. His work offers a softened, sympathetic narrative of humanity’s deep geologic past.

Cro-magnon artists painting in Font-de-Gaume, France. (Art by Charles Knight, 1920. From here)

Cro-Magnon artists painting in Font-de-Gaume, for example, shows the early ancestors of modern human and invites the viewer into the scene through the front-and-centre point of view. Situating his Cro-Magnon subjects in the centre field immediately imbeds the viewer as a member of the clan; part of the visual narrative. Moreover, Knight painted many Neanderthal portraits and murals – he considered himself immensely sympathetic to the evolutionary plight of what he saw as a doomed species. As such, his Neanderthal landscape paintings contain a pathos that many early twentieth-century reconstructions lacked – Knight’s Neanderthals have dignity without caricature. Knight considered the Neanderthal evolutionary trajectory of extinction tragic, but inevitable.

A detail from the beautiful giant mural ‘The Flint Workers of the River Vezere.’ The mural at the American Museum of Natural History was restored in 1994. (Art by Charles Knight, 1920. Image from here)

The Pleistocene landscapes and murals of Charles Knight act as cultural touchstones, even as the science of the megafauna and hominins evolves. His work is ubiquitously present in many iterations of many paleo disciplines and illustrates a brilliantly understated, carefully studied, and sympathetic portfolio of the Pleistocene.

Written by Lydia Pyne (@LydiaPyne)

Edited by Jan Freedman (@janfreedman)

This is an expanded version of a blog post from http://www.pynecone.org/blog.

Further Reading:

Gould, S. J. (1990), ‘Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History’, New York: W.W. Norton & Company 1990. [Book preview]

Knight, C. R. (1935), ‘Before the Dawn of History’, New York, London: Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc. [Book]

Milner, R. & Knight-Kalt, R, (2012), ‘Charles R. Knight: The artist who saw through time. New York: Harry N. Abrams. [Book review]

Osborn, H. F. (1915), ‘Men of the Old Stone Age: Their Environment, Life, and Art’, New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons. [Full book]

Reblogged this on FromShanklin.

Reblogged this on Piedras de papel.

Pingback: The Nipple Tooth | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: The iconic woolly mammoth | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Crash of the Titans | TwilightBeasts

Fantastic article, and great blog!

Pingback: Dire times for bone crushing dogs | TwilightBeasts