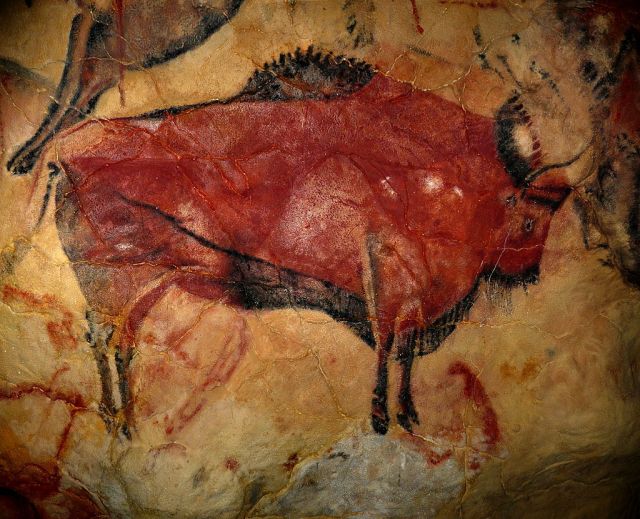

Beautiful cave painting of the magnificent steppe bison, Bison priscus. (Image from here)

A long time ago, 1879 to be precise, a little girl and her father were exploring a cave in Spain when she gasped in amazement “ Look, daddy! Bulls!” The images she saw for the first time in about 16,000 years were cave paintings in red ochre of prancing creatures of the steppe and tundra. The cave was Altamira, in Spain, and the bulls were Bison priscus, the steppe bison, which is one of the predecessors of the iconic modern bison we know today. It gets complicated, actually – the modern bison in Europe is likely closer related to Bison priscus than the American bison, which comes down to us today via a different evolutionary path!

Imagine a huge ruminant over 2 metres tall at the shoulders, with the adult males having a huge horn span of about 1m, horns curving lethally outwards at the tips – all the better for goring you with. These are the Pleistocene bison shown attacking humans in cave art at Lascaux and Villars. The shoulders had two powerful humps of solid muscle from the withers back, and longer hind legs than todays bison (but similar to the only other living species of bison; Bison bonasus, or European wisent) these were aggressive bovine warriors on the moo-ve.

The steppe bison, Bison priscus, were creatures well suited to the cool steppe grasslands from 2 million years ago to their eventual extinction about 10,000 years ago. They were found across Europe and Eurasia, from where they crossed the Beringia land-bridge and lolloped across the grasslands of North America with equally large Pleistocene creatures such as mammoths and mastodons. Assemblages of pollen in the stomach of a well preserved carcass from the frozen Indigirka Rover in Siberia have shown that like bison around today, our shaggy Twilight Beast, Bison priscus, liked grasses and hardy little wild herbs of the Brassicaceae and Chenopodaceae families to graze on. Blue Babe, the most famous –and frozen steppe bison to date had a post-mortem dental check, which showed he’d been munching on dry grasses such as Agropyron and Danthonia. As Blue Babe was a big Alaskan bull, it’s interesting to note that these grasses still grow plentifully in the Yukon and Alaska to this day.

Blue Babe was found near Pearl Creek, Alaska, in 1979. He takes his name from Paul Bunyan’s legendary ox who was so huge he could haul anything, and the ‘blue’ part because he was covered in a sapphire blue mineral deposit which had assisted the preservation considerably. This 36,000 year old beast was apparently so well frozen that a chunk of shoulder steak was cooked and eaten by the excavation team! (We’ve really no idea if this is truth or bravado, though!) That being said, if the excavators did tuck into prime 36,000 year old steak, they weren’t the first Homo sapiens to do so. Our ancestors exploited Bison priscus as food. Not only are there indications of flint points in the carcasses and bones of specimens in Siberian specimens, but there is also considerable evidence of hunting and butchering at the Schoningen 13 Palaeolithic hunting settlement excavated sporadically from 1992 onwards.

As an archaeologist writing for this blog, I always tend to look at the animals which had close links to humans, the creatures which meant something to the tenacious ancient people. It’s to be suspected that Bison priscus would have been quite a trophy for a hunter. These bovines would not have been a walkover to take down; a scene at Villars shows a mortally wounded steppe bison savagely goring a fallen hunter. Our ancestors must have watched and waited opportunistically to hunt these creatures which were formidable opponents to Ice Age humans, yet agreeable and gregarious among their own kind, until rutting! There are beautiful images of these massive creatures all over Europe: an engraved bone fragment from Le Morin depicts a mummy bison and a little baby one (which were very sweet indeed by the looks of the artwork!). A fabulously observed image at Le Portel Caves shows two horny bulls clashing during the rut, with swishing tails. But perhaps my favourite of all is a piece of mobiliary art, made of clay, showing a male mega-moo wooing a lady steppe bison. This was found at Tuc d’Audoubert, France. The figures, in all their vitality, date to 15,000 years ago, and may very well be some sort of fertility magical figures.

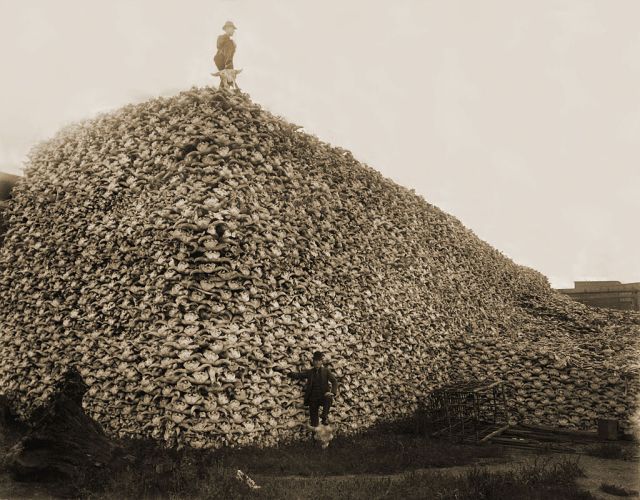

So, what caused the end of these splendid bovines with serious attitude? The steppe bison was evolved to cope and thrive on wide open grasslands. The changes in climate post Younger Dryas resulted in boreal forests springing up across Europe in particular. The last known steppe bison were found in Dakota, dating to some 8,000 years ago. Climate change was likely the main feature in their extinction, although it’s likely that the most lethal animal of the Holocene, mankind didn’t do them any favours either. We just have to think how the plains bison were hunted to near extinction by descendants of post-medieval European colonists in the USA. While indigenous peoples would have shared the land with these magnificent animals understanding the breeding seasons and environmental factors needed to sustain them, newly arrived colonising peoples may very well have hunted for sport, not food.

A terribly sad photograph of an enormous pile of unfathomable American bison skulls in the 1870s, waiting to be ground into fertiliser. (Image from here)

When we look at the reintroduction of the American plains bison today, we can imagine what an awe inspiring sight the Ice Age peoples would have witnessed as the herds sought their favourite grasses. As it is, we still have the wonderful sympathetic art our ancestors left, drawn in red ochre,– the ultimate ‘red bulls’ snorting with energy and vibrance!

Written by Rena Maguire (@justrena)

Further reading:

Excavation of Bison priscus skull from permafrost.

Begouen,R; Fritz,R; Tostello,G, Clottes,J, Pastoors,A and Faist,F. 2009. Le Sanctuaire Secret des Bisons Il y a 14,000 ans dans la cavern du Tuc D’Audoubert. Paris: Somogy D’Art. [Book]

Boeskorov, G., Potapova, O., Protopopov, A., Kolesov, S., & Tikhonov, A. 2012. ‘The Yukagir Bison: A complete frozen mummy of the extinct Bison priscus from Yakutia,Russia’. Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 32. 65-66. [Full article]

Boeskorov, G. G., Potapova, O. R., Mashchenko, E. N., Protopopov, A. V., Kuznetsova, T. V., Agenbroad, L., & Tikhonov, A. N. 2013. ‘Preliminary analyses of the frozen mummies of mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), bison (Bison priscus) and horse (Equus sp.) from the Yana‐Indigirka Lowland, Yakutia, Russia’ . Integrative zoology. [Full article]

Guthrie, D. 1990. Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe: The Story of Blue Babe Chicago : University of Chicago Press. [Book]

Kolfschoten, I; , Knul,T; Buhrs,M; and Gielen, M. 2012. ‘Butchered large bovids (Bos primigenius and Bison priscus) from the Palaeolithic throwing spear site Schoningen 13″-4 (Germany)’ in. Raemaekers D;. Esser, E, Roel C; Lauwerier,G and Zeiler, J.T (eds) A Bouquet of Archaeozoological Studies: Essays in Honour of Wietske Prummel Groningen: Barkhuis Publishing. [Book]

Kurtén, B. 1968. Pleistocene Mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London. [Book]

Kurtén, B. and E. Anderson. 1980. Pleistocene Mammals of North America. Columbia University Press, New York. [Book]

Leroi-Gourhan, A. 1982. The Dawn of Paleolithic Art. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Book]

Van Geel,B; Protopopov,A; Bull, I; Duijm,E; Gill,E; Lammers,Y; Nieman,A; Rudaya,N; Trofimova,S; Tikhonov,A; Vos,R and Zhilich,S. 2014.’Multiproxy diet analysis of the last meal of an early Holocene Yakutian bison’ Journal of Quaternary Science. 29.3.261-268. [Abstract only]

Windels, F., & Laming-Emperaire, A. 1950 The Lascaux cave paintings. Viking Press. [Book]

You write very well. Do you have other sites that are similar?

Reblogged this on Homeschool Mirth.

Pingback: Paddington’s dangerous cousin | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Just like the weather | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Ghosts of the Desert | Michelle María Early Capistrán

Pingback: The beauty in the beasts | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: From the bones of giants | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Did humans wipe out the megafauna? | TwilightBeasts

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through a few

of the articles I realized it’s new to me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely pleased I discovered it

and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back often!

Pingback: Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? A true story of the real Palaeolithic diet! | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Amidst the footsteps of giants: What beetles can tell us about the past | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Getting inside the bones | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Stuck in time | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Lost Landscapes | the incurable archaeologist

Pingback: Standing Proud | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Smilodon: The Iconic Sabertooth | TwilightBeasts