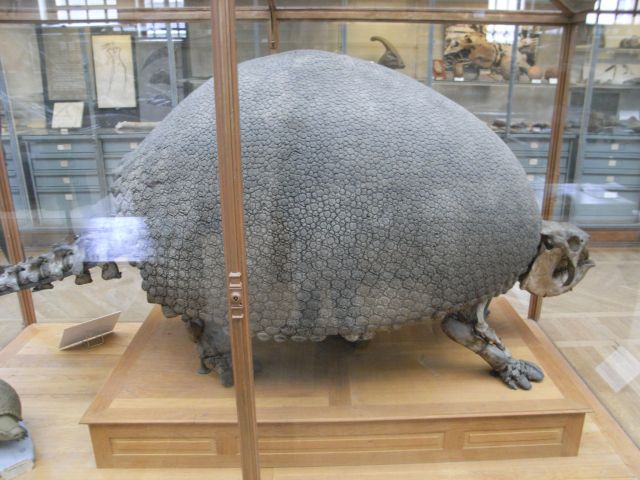

Imagine an igloo. Now picture it with a crash helmet poking out the front, and a medieval spiked club sticking out the back. Elevate that image on four stubby legs, convert it into bone and flesh and you have a good approximation of a glyptodont. For my money the weirdest extinct animal that humans encountered on their global tour. Relatives of sloths and anteaters, glyptodonts are grouped with them in the taxonomic superorder Xenarthra due to shared features such as a lack of tooth enamel, extra articulations on their vertebrae, and (presumably) males with internal testicles.

Reconstruction of Glyptotherium sp. by Sergiodlarosa

Found all over South America, having evolved in isolation there during its long history as an island continent, the glyptodonts ranged as far north as South Carolina during the Pleistocene. At least three genera are known to have survived up to the late Pleistocene: Panochthus, Glyptodon(Glyptotherium), and Doedicurus. Despite superficially looking identical, these three genera packed their punches in pretty different ways. Glyptodon had a tail made from concentric rings of spiky bone with a fringe of points around its carapace. Doedicurus had a long cylindrical tail club with enigmatic circular depressions over the end (probably indicative of enormous keratin horns that grew during life). Panochthus was a mix of spiky tail rings and a cylindrical, horny, club. This was the business end of the glyptodonts and ensured that an adult probably had no natural predators. However, the young ones were hunted- there is a famous subadult Glyptotherium texanum skull from Southeastern Arizona that has two neat, elliptical holes punched in the top. They exactly match the only predator with elliptical canines from that timeframe- Smilodon fatalis. Interestingly, this method of attack is sometimes used by the extant jaguar (Panthera onca), which will kill capybara and other medium-sized prey by piercing the braincase through the ears. Could jaguars have honed this method on another, now extinct, species that formerly shared its range?

With such powerful predators around, growing glyptodonts would have been glad of their mammalian thagomizers. It seems likely that as well as a defensive weapon, the tail clubs were also used in intraspecific competition. Some carapaces show traces of damage that match the size and shape of another animals tailclub. Researchers have calculated that a single blow from the tail of one species, Doedicurus clavicaudatus, could produce 60 kiloNewtons of force (by way of comparison, 4 kiloNewtons is enough to fracture an average human femur). There is even evidence that the tail evolved to produce an offensive weapon analogous to a baseball bat, with a centre of percussion at the exact point where the spikes began, allowing it to transmit maximum force with each blow.

Fossil of Doedicurus clavicaudatus, showing the tail club with spike positions. Image from here

The glyptodonts appear incredibly weird to modern eyes. How might they have been viewed by the paleoindians who encountered them? There is surprisingly little “good” archaeology on interaction between them and man. However, some less than charming vignettes are suggested. The famous palaeontologist Florentino Ameghino claimed to have found two examples of the carapaces of glyptodonts used as temporary shelters! He recounts finding the detritus of occupation: flints, cutmarked bones, and charcoal around a glyptodont shell excavated close to the town of Mercedes, by Buenoes Aires in Argentina. He surmised that the glyptodont had been hunted by people, who then dug a small pit and roofed it with the carapace to provide shelter on the treeless pampas. There is also evidence of the use of glyptodont osteoderms (the hexagonal bones that make up the carapace) as grave offerings (at the site of Arroyo Seco 2 in Argentina).

Such an incredible creature, and it stopped you getting sunburnt too.

Written by @DeepFriedDNA

Further Reading:

http://www.azgs.az.gov/arizona_geology/spring10/article_feature.html

http://www.wired.com/2011/02/extra-armor-gave-glyptodon-an-edge/

Marquis de Nadaillac (1884), “Prehistoric America” [Book]

Gillette, D. & Ray, C. E. (1981) “Glyptodonts of North America” Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology #40 [Full Article]

Fariña, R. E., Vizcaino, S. F., & De Iullis, G. (2013) “Megafauna: Giant beasts of Pleistocene South America” [Book]

McNeill Alexander, R., Fariña, R. E., & Vizcaino, S. F. (1999) “Tail blow energy and carapace fractures in a large glyptodont (Mammalia,Xenarthra)” Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 126, 41-49 [Abstract]

Blanco, R. E., Jones, W. W., & Rinderknecht, A. (2009)”The sweet spot of a biological hammer: the centre of percussion of glyptodont (Mammalia: Xenarthra) tail clubs” Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B 276, 3971-3978 [Abstract]

Huxley, T. H. (1865) “On the osteology of the genus Glyptodon” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 155, 31-70

Politis, G., & Gutiérrez, M. (1998) “Gliptodontes y cazadores-recolectores de la región pampeana (Argentina)” Latin Am Ant 9, 111–134

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 26/09/2014 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast

Pingback: Darwin’s 18 pence | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: The strangest animals ever discovered | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: The long reign of terror | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Did humans wipe out the megafauna? | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Survivors | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: How to weigh a Dodo | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Going underground | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Turtle Power | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Giant Sloths & Sabertooth Cats | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Horned Armadillos and Rafting Monkeys | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: Remarkable creatures | TwilightBeasts

Pingback: The forgotten dogs of South America | TwilightBeasts