In 1835 the young, and somewhat cavalier, Charles Darwin landed for the first time on the Galapagos archipelago. As well as sending hundreds of specimens back to England, Darwin enjoyed exploring the islands and watching the local species in their natural habitat. Arguably one of the most magnificent animals he set eyes on were the giant tortoises. In his zoological and geological write up, The Voyage of the Beagle, he dedicates quite some space to these enormous reptiles.

Darwin observed them and studied them closely.

He also rode them.

Yep. Charles Darwin rode on the back of giant tortoises.

“I frequently got on their backs, and then giving a few raps on the hinder part of their shells, they would rise up and walk away;- but I found it very difficult to keep my balance.”* (Darwin, 1839)

Giant tortoises are pretty big. Big enough to straddle. (Please don’t ever straddle one.) On the several islands of the Galapagos archipelago there were 13 different species of giant tortoises, with at least 2 of these only recently becoming extinct. What’s more amazing is that the giant tortoise is not just restricted to the Galapagos archipelago. Another species lives on the Aldabra atoll, in the Indian Ocean: the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea). Until just a few hundred years ago there were giant tortoises on several islands in the Indian Ocean, before humans arrived.

Not all giant tortoises live in the Galapagos archipelago: the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea) from the Seychelles.(Image Public Domain)

Once there were many more species slowly lumbering around. And slowly lumber they did: they started to vanish around 100,000 years ago with most becoming extinct by around 10,000 years ago. It seems they were easy pickings for one species of bipedal ape. Our beast was pretty similar to the Galapagos giant tortoise, only, much, much bigger. This was the largest giant tortoise ever: Megalochelys atlas.

This was a very successful genus spanning the Miocene (around 5 million years ago) to the Late Pleistocene (around 10,000 years ago), living in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and possibly as far west as Europe. With a similar anatomy to the Galapagos giant tortoise, this extinct beast likely ate similar food: dried leaves on the forest floor with the huge stocky limbs holding up their enormous house.

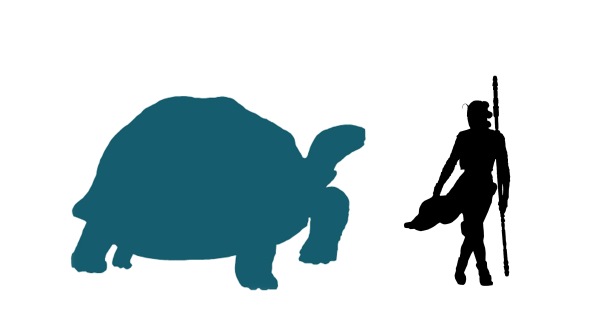

The enormous giant tortoise Megalochelys atlas shows just how big it was compared to Rey. (Image by Jan Freedman)

But why did they get so big? Familiar gigantism in animals is seen on islands (unimaginatively known as island gigantism). Here, isolated on an island a normally small mainland animal becomes pretty darn big. We have seen this in a number of our beasts: the dodo (being an oversized pigeon); the giant lemur of Madagascar; the huge Hawaiian Duck; the massive flightless Moa; and many more. Some animals will quickly get bigger in their new environment due to lack of predators and new and plenty foods around.

These ginormous tortoises didn’t live on small islands; they lived on a continent. Animals can grow pretty big on large landmasses too. You might be familiar with those pesky animals that get all the media love: dinosaurs. Some of these grew to unfathomable sizes for animals, where each new discovery pushes the limits to how big an animal can get. Proboscids, like Mammoths and the giant Zygolophodon, also grew to massive sizes. Perhaps there is no specific reason for these tortoise growing so large, except that they could. In good times species flourish, and Miocene Eurasia was a rich fertile environment which doubtless supported these (and many other) incredible creatures. Today we find the giant tortoises isolated on islands and assume this is how they got their crazy big sizes. But they got big on the mainland first, and later arrived on islands by chance.

Despite first being discovered back in 1844 there is not that much information about this massive giant tortoise. There is no mention of it in any of my Pleistocene books on my bookshelf, and relatively few references in the literature. They were very likely similar to their island relatives in lifestyle. The giant tortoises on the mainland became extinct between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago, likely by the hand of humans although no roasted shells have yet been discovered.

What saved the giant tortoises alive today from extinction were the islands they made home. But even then soon after humans arrived many island populations vanished forever. When Darwin was on the Galapagos, he notes how sailors brought dozens of giant tortoises down to the ship with relative ease. Previous years, they were so abundant that sailors had caught around 600 tortoises. They were so easy to catch because they relied on their size to protect them and they had no reason to fear humans. These giants were a favourite of sailors to take back for fresh meat on their long voyage home: the tortoise lived on the ships without the need of much attention, and gave the crew fresh meat when needed. They were easy pickings for sailors, and no doubt that Megalochelys atlas was easy pickings for the first Homo sapiens who encountered them in Eurasia. I often wonder if any of these people were gutsy enough to hop on and straddle the biggest tortoise to have ever lived.

Written by Jan Freedman (@JanFreedman)

Further Reading:

Arnold, E. N. (1979), ‘Indian Ocean giant tortoises: Their Systematics and Islands Adaptations,’ Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 286: 1011, The Terrestrial Ecology of Aldabra (Jul. 3, 1979), pp. 127-145.

Badam, G. L. (1981) ‘Colossochelys atlas, a giant tortoise from the Upper Siwaliks of North India,’ Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 40. pp.149 – 153.

Falconer, H. & Cautley, P.T. (1844). ‘Communication on the Colossochelys atlas, a fossil tortoise of enormous size from the Tertiary strata of the Siwalk Hills in the north of India.’ Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 12. pp.54–84.

Hansen, D. M., et al. (2010). ‘Ecological history and latent conservation potential: large and giant tortoises as a model for taxon substitutions.’ Ecography. 33:2. pp.271-284.

West, R., Hutchinson, H., & Munthe, J (1991) ‘Miocene vertebrates from the Siwalik Group, Western Nepal,’ Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 11: 1. pp.108-129.

Very big thanks Writers. I like toryouse. Have 4 at home.

This is a neat blog. Glad I found it.

Pingback: Fossil Friday Roundup: July 7, 2017 | PLOS Paleo Community

Pingback: Fossil Friday Roundup: July 7, 2017 | PLOS Blogs Network

Pingback: On the dhole | TwilightBeasts